The Participatory Engagement of City Communities Against Non-Communicable Disease Risk in Bangladesh and Nepal (PECAN) Project is an implementation research initiative based on the principles of citizen science. It aims to equip policymakers, practitioners and citizens with evidence-based, equitable and sustainable strategies for promoting health and reducing NCD risk.

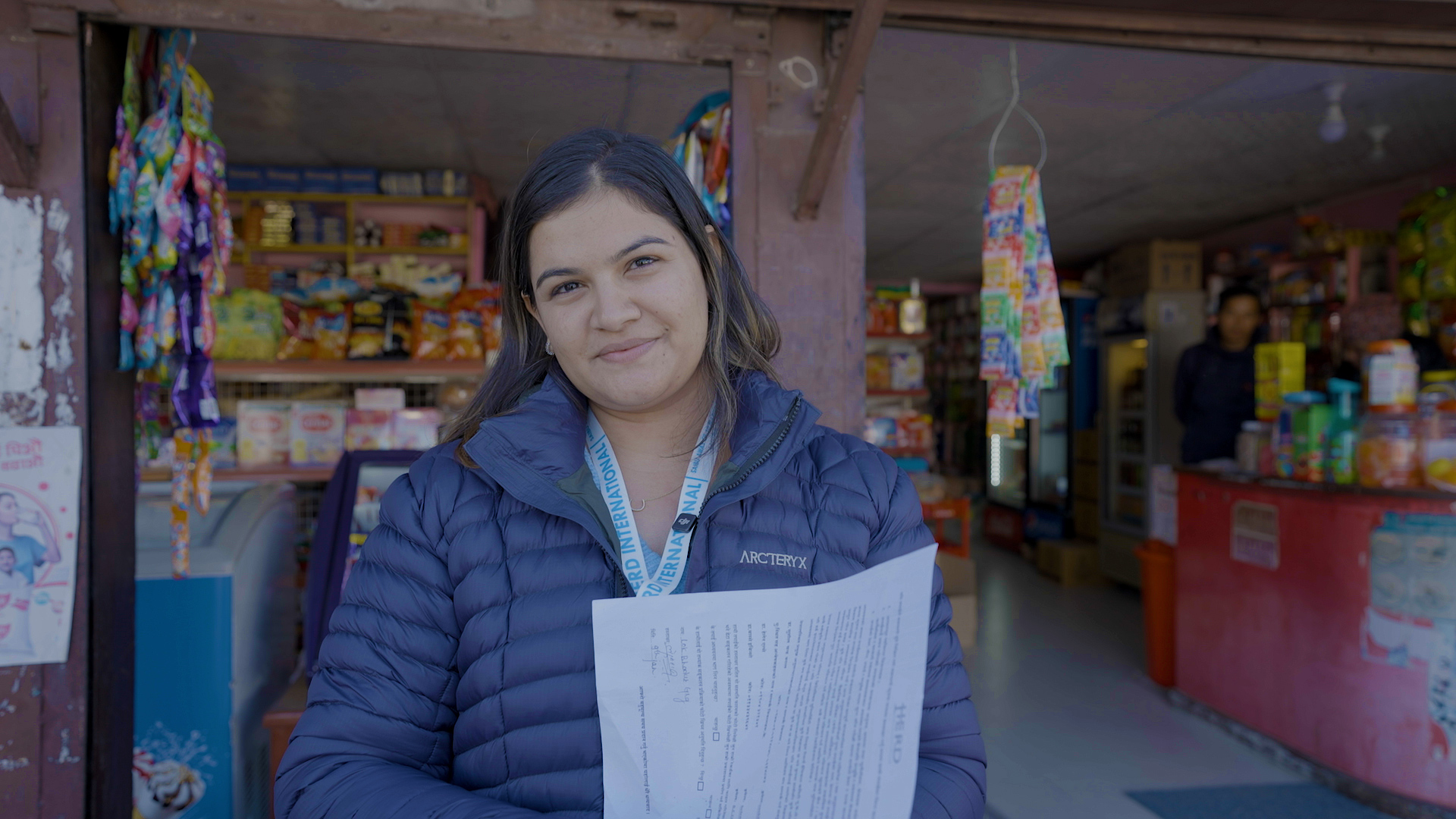

HERD International selected and trained young public health professionals to conduct a census in two wards of Nagarjun Municipality and one ward of Kathmandu Metropolitan City. Two of the researchers, Irica Neupane and Raymond B C, reflected on their experiences and shared their biggest takeaways.

Irica Neupane

Data collection in urban areas comes with its own set of challenges that are different from rural settings. Urban fieldwork is marked by the rapid pace of people’s lives, which researchers must mirror in their movement and their approach to interviews. Oftentimes, participants selected for interviews are protective of their privacy, meeting unknown researchers with suspicion and uncertainty.

However, during my time collecting data in Nagarjun Municipality and Kathmandu, there were several occasions where I was able to overcome these suspicions and build true connections with a simple approach: I started and maintained each interaction with a genuine smile.

I had an unforgettable encounter was with an elderly woman, someone I now fondly call Ama (mother). As I called out from the gate, asking if anyone was home, I noticed a head peek through the window curtain upstairs. A pause. Then the door creaked open and she slowly walked down the stairs. “I came down just for the smiling lady who called,” she said, her eyes twinkling.

At first, she refused to participate in the survey. She voiced frustration about the government and how it had long neglected the community. “Why should I help the government? It does nothing for people like us.”

But then she looked at me again and added, “But you, your sweet smile and that kind voice of yours—that’s why I’m giving you this data. Had it been someone else, I would’ve shooed them away.”

That moment humbled me. A smile and sincerity had opened a door where logic and persuasion might have failed.

On another occasion, I interviewed a couple at their home which joined up with a small, local pub. When I first arrived, I hesitated to cross the threshold. I braced myself for their suspicion or the effects of intoxication. To my utter surprise, they welcomed me with true warmth. Wary of the surroundings and the strong smell of alcohol, the wife warned me lovingly, “It might stink in here.”

She was caring enough to warn me about the smell, asking if it might make me uncomfortable. I smiled warmly and reassured her it was completely fine, and that they were free to continue their daily routine. At one point, the husband jokingly asked, “Do you drink as well, sister?”, and the whole room burst into laughter.

As we continued the interview, they proudly showed me a picture of their daughter in the US and told stories of their son who once demanded an expensive guitar. The husband kept teasing his wife, complimenting her beauty, reminiscing about the boys who liked her, even joking about his old flame. What touched me the most, however, was that de introduced her as the head of the household openly, proudly, and without a flicker of ego.

Their love, their respect, their mutual teasing and tenderness—they were all reminders that surveys are not just about data points. They are windows into lives. Their warmth and kindness also taught me to always withhold judgement about how people live and behave.

We often think fieldwork is just about the challenges—walking long distances, managing rejections, recording accurate data. This experience taught me that fieldwork is also about people and the powerful human connections that make the work meaningful. I was able to break barriers with just a smile and calm demeanor, and I will carry that with me for the rest of my career. And for me, those moments became more than just stories—they became memories,

memories I now carry with me like field notes for life.

Raymond B C

I began my work on the PECAN project with a mix of excitement and nervousness. Our team was collecting data in the busy and diverse urban areas of Kathmandu Metropolitan City Ward 14 and Nagarjun Municipality Wards 9 and 10. As I stepped into these communities, it felt like I saw the real Nepal—alive, complex, and deeply human. These neighborhoods were mirrors of our country’s diversity.

People from all 77 districts have gathered here: families from the snowy Himalayas, the green hills, and the hot plains of the Terai. Within just a few days, I met people from all walks of life; some who had never been to school, others with high school or vocational training, others with master’s degrees and PhDs. Teachers, laborers, shopkeepers, housemaids, doctors, engineers, other professionals, and unemployed youth all live side by side, sharing the same neighborhood but carrying very different life journeys.

The city feels like a living tapestry of inequality, diversity, and resilience, all woven into narrow streets and multi-story buildings. I could hear Bhojpuri from one room and Tamang songs from another. It was beautiful, but also overwhelming. The richness of diversity comes with deep layers of social and economic inequality.

I entered homes where five or more families lived in a single dark room, separated only by bedsheets, with no windows or proper ventilation. I also visited houses with furnished rooms, cool air, and neatly placed photo frames. On every street, I saw three versions of Nepal: one struggling, one surviving, and one thriving. Somehow, these versions all lived side by side.

Planning our work in this setting required more than just following a schedule; it required understanding people’s lives. We visited working families, government employees, private sector workers, informal laborers, gig workers, and blue-collar professionals, usually early in the morning or on Saturdays when they were home. Some mothers were often available during the day but were always busy cooking, washing, feeding. I conducted several interviews while standing at the gate or main door of a house, with a data collection tablet and consent forms in hand, often next to children doing homework, playing, or babies crying. It was not always smooth, but when I slowed down, listened, and smiled, people opened up.

Some did not want to answer questions and asked a family member to respond instead. Others were in a hurry, while some were very curious and even offered suggestions on how to approach their neighbors. Every household was different, so we adapted our communication style based on trust, willingness, and comfort. Although some residents were initially skeptical or fearful, once we built trust, we felt a true sense of belonging. It no longer felt like we were just collecting data, but that we were becoming part of their community and carrying their stories and concerns with us.

Most doors were answered by women, primarily wives, mothers, and grandmothers. Some were widows or elderly women living alone. I often met elderly couples, both sick and living with chronic conditions, their children abroad. Some could not hear well, some forgot things, and some just wanted to talk to because they were lonely. I learned very quickly to see that they were not just participants, they were people who needed to be seen and heard.

I still remember the old man who teared up while talking about his son in America who had not visited in ten years. I remember the woman stirring lentils on the stove while explaining her blood pressure problems. I remember the wide-eyed, curious teenager who asked if he could help us with our work. We did not just conduct interviews, we saw into lives full of strength and quiet struggle.

Fieldwork is tough. Many houses were locked, some had no doorbells. We had to knock, call out, and wait patiently. Dogs barked at us, sometimes chased us. Our feet grew tired, and community members watched us with skepticism. We were always careful, sometimes even scared. The heat of early summer burned our backs, and sudden rain often washed away our plans. But we returned, day after day. With GPS in hand and support from our team, we mapped, visited, and covered every corner we could.

Technology helped us stay organized, but it was people who made the difference. My teammates, local government staff, and project officials worked closely together, helping us reach people respectfully. Local leaders gave us trust and entry. Without their support, none of this would have been possible.

Through the PECAN project, I learned that data is more than statistics; it holds real human stories of migration, illness, joy, and resilience. Each data point represents a lived experience, often shared when we approached with patience, empathy, and active listening. I discovered that gentle communication and respect could open doors to trust, even in the most challenging environments. I always told myself to go slow, be patient, listen more than you speak, and learn the rhythm of the community. This journey taught me to value the emotions and struggles behind each response, making the process deeply personal and transformative.

Comments (0)

No comments found.